Well before his vanishing, legend coiled around him his reports and speculations may have prompted his friend Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to write “The Lost World” (1912), the precursor of “Jurassic Park.” You could equally frame Fawcett as desperate, deluded, and ill-prepared. Z, for him as for other explorers, is what you dream it to be, and Fawcett, in turn, is open to transformation. He stands in the shadows of his hallway, and something gleams behind him-the leaflike blade of a spear. When Fawcett returns after one expedition, the front of his English house is wreathed in creepers, as if the tendrils of vines had spread across the sea. Whichever continent we are in, we sense the gravitational pull of another. For the purposes of the film, these have been compacted to three, and what excites Gray’s imagination is the clash-or, stranger still, the momentary merger-between distant cultures. Does this fair bit of action, however, mean that “The Lost City of Z” counts as an action movie? It seems more like a study in restlessness. Still to come: white-water rapids, an inquisitive panther, and a surprisingly cheerful sojourn with practitioners of cannibalism. It is not long before arrows are thrumming toward him from the banks of the Amazon, fired by the indigenous people into whose land he and his men have drifted. Summoned to the Royal Geographical Society, and asked to survey an unmapped region of Bolivia, he says, “I was rather hoping for a position where I might see a fair bit of action.”

Worse still, he has been, as someone remarks, “rather unfortunate in his choice of ancestors.” His father was a gambler and a drunk, and Percy must redeem the family name. A dull run of military postings has left him with no medals. He lusts for glory, but only his own, and a mass of wounded feelings is encased in his tough hide. We gather at once that Fawcett is bold, impatient, and chafed by recklessness. Here, as in a later scene at the Battle of the Somme, Gray shows himself to be a master of the moral sketch: a burst of decisive visual gestures that give us the character of a person. We first encounter Fawcett, suitably enough, on another hunt-on horseback, racing across the Irish countryside on the trail of a stag. It is best approached, I would say, as a fantasia on Fawcettian themes.

#Aftermath 2017 movie

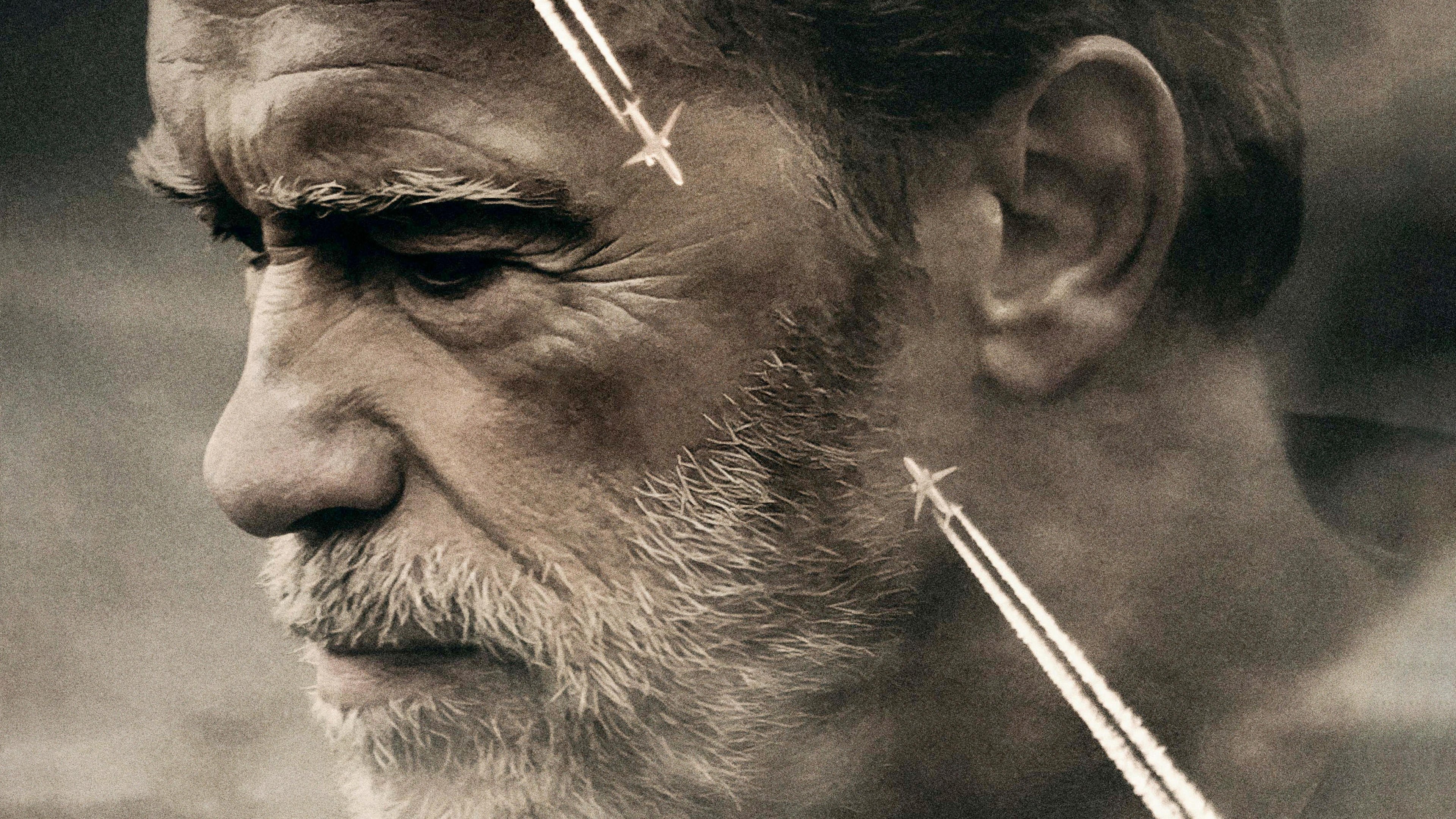

Yet the movie that results should not be combed for historical truth. Gray has borrowed the title, and he dramatizes many of the episodes to which Grann and other writers have referred. Fawcett’s exploits were described by David Grann in this magazine in 2005 and subsequently in his book “The Lost City of Z” (2009). He was convinced that the remains of a forgotten civilization lay concealed in the rain forest, and it is generally assumed that he lost his life in pursuit of that belief he and his eldest son, Jack (Tom Holland), were last seen venturing into the jungle in 1925. The hero is Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam), a British soldier who journeyed up the Amazon at the start of the twentieth century and, like other questing souls before and since, became obsessed. What’s going on? If Gray continues like this, his next project will be shot in Alpha Centauri. Much of the story unfolds in the depths of Amazonia other locations include Ireland, London, and the English countryside. The jungle in question is the real deal: steamy, infested, and perilously short of good delis. Interesting choice.” Little did they know. Admirers of Gray (a select but ardent bunch), upon learning that he was busy filming in the jungle, will have said to themselves, “Hmm, the Bronx Zoo. He made it all the way to the Lower East Side.īy any standard, therefore, his latest movie, “The Lost City of Z,” comes as a shock. It was not until “The Immigrant” (2013) that Gray spread his wings and took flight. Nor could the agonized “Two Lovers” (2008). “The Yards” (2000), which confounded everything you’ve heard about the curse of the sophomore work, was more adventurous, travelling as far as the Bronx, but the third film, “We Own the Night” (2007), kicked off in Brooklyn, once again, and could hardly tear itself away.

His début feature, “Little Odessa” (1994), was set in Brighton Beach. Until now, the films of James Gray, who was born in Queens in 1969, have stayed close to home.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)